This essay was originally posted in November 2015 on ActiveHistory.ca.

Following the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report six months ago, universities across the country are re-evaluating our practices. Both individually (as recently seen at the University of Winnipeg and Lakehead University) and collectively through Universities Canada’s broad response to the commission’s final report, campuses across the country seem to be making a more concerted effort to respond to this call for change. Perhaps most directly for readers of ActiveHistory.ca, it is the 62nd and 65th calls to action that most directly affect our work as historians and history teachers. Call to action 62 focuses on the importance of collaboration between survivors, Indigenous peoples, educators and governments to provide resources, research and funding to equip teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary to redevelop curriculum and integrate Indigenous knowledge and pedagogies into the classroom; while 65 calls on the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, in a similarly collaborative approach, to establish a national research program focused on reconciliation.

Following the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report six months ago, universities across the country are re-evaluating our practices. Both individually (as recently seen at the University of Winnipeg and Lakehead University) and collectively through Universities Canada’s broad response to the commission’s final report, campuses across the country seem to be making a more concerted effort to respond to this call for change. Perhaps most directly for readers of ActiveHistory.ca, it is the 62nd and 65th calls to action that most directly affect our work as historians and history teachers. Call to action 62 focuses on the importance of collaboration between survivors, Indigenous peoples, educators and governments to provide resources, research and funding to equip teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary to redevelop curriculum and integrate Indigenous knowledge and pedagogies into the classroom; while 65 calls on the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, in a similarly collaborative approach, to establish a national research program focused on reconciliation.

Alongside survivor and Elder testimony, history and its practice are central to this report. In a recent talk here at Western, J.R. Miller noted that both in the TRC’s final report and the Royal Commission Report on Aboriginal Peoples, the revisionist work of academic historians feature prominently. He’s right. In addition to Miller himself, scholars like James Axtell, John Borrows, Sarah Carter, Denys Delâge, Robin Fisher, Cornelius Jaenen, Mary-Ellen Kelm, Maureen Lux, John Milloy, Toby Morantz, Daniel Paul, John Reid, Georges Sioui and Bruce Trigger among others reshaped Canadian historiography over the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Their work laid the groundwork that – in part – has caused us to rethink and revise how Canada’s history is understood.

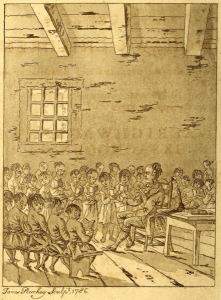

And yet, despite this historiographical shift, its influence on the broader structure of Canadian history seems minimal. The place of Indigenous peoples and perspectives flushed out in greater detail, perhaps, but still relegated to a few key moments and periods in Canada’s past. A cursory look at a handful of textbooks in the field, for example, makes the point most clearly.[1] Though textbooks have certainly improved their overall coverage of Indigenous peoples, few have made a substantial revision to their overall structure, only featuring Indigenous peoples as a prominent part of the discussion in a handful of places: European discovery, missionaries and the fur trade, and then interspersed throughout the pre-Confederation period; discussion peters out for the most part in the post-Confederation textbooks until the 1960s/70s (some as late as the 1990s), when Indigenous resistance and political action re-emerged. In today’s post I would like to build on these observations, which are also made in the TRC’s report (pages 234-239 and 246-258), by posing a simple question: How do the TRC’s findings and calls to action shape our teaching of the Canadian history survey course?

Continue reading “Truth and Reconciliation while teaching Canadian History?” →

Following the release of the

Following the release of the